Who’s getting missed?

It’s a question the Health Fund is always asking—whether it’s access to behavioral health treatment or a mode of transportation to the doctor’s office, we want to know where the gaps are so that we can work to help to fill them.

That’s why we commissioned MPHI to create the Michigan Food Environment Scan. This new report provides a sweeping overview of the hundreds of food interventions currently underway in Michigan, paying special attention to the communities falling between the cracks.

As COVID-19 continues to make existing food system challenges even more pressing, this report offers a timely analysis of what’s working, what we need more of, and where we need it. It’s part of our ongoing effort to stay informed on the state of Michigan’s health in order to guide our future investments.

Here are some of the key takeaways:

MICHIGAN ORGANIZATIONS ARE WORKING HARD…

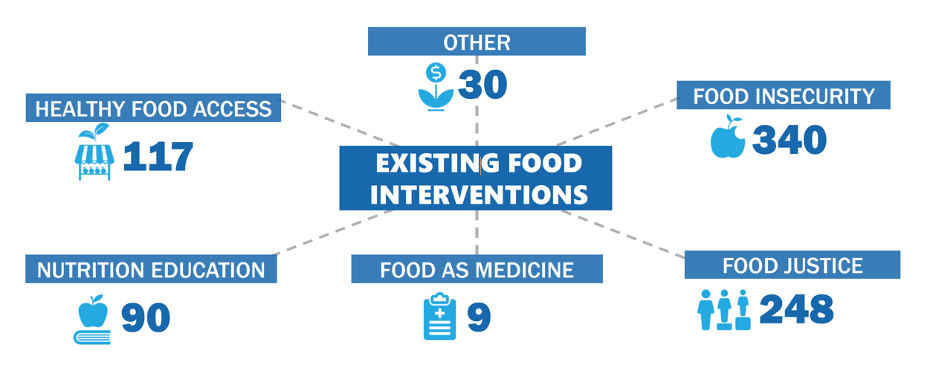

MPHI catalogued 583 unique Michigan food interventions run by 465 nonprofits, universities, and government agencies. They sorted those projects into six categories of work: healthy food access, nutrition education, food as medicine, food justice, food insecurity, and “other,” with some falling into more than one category.

12 of the organizations implement multiple programs, including three that run more than four—Gleaners Community Food Bank, Michigan State University, and Food Bank of Eastern Michigan.

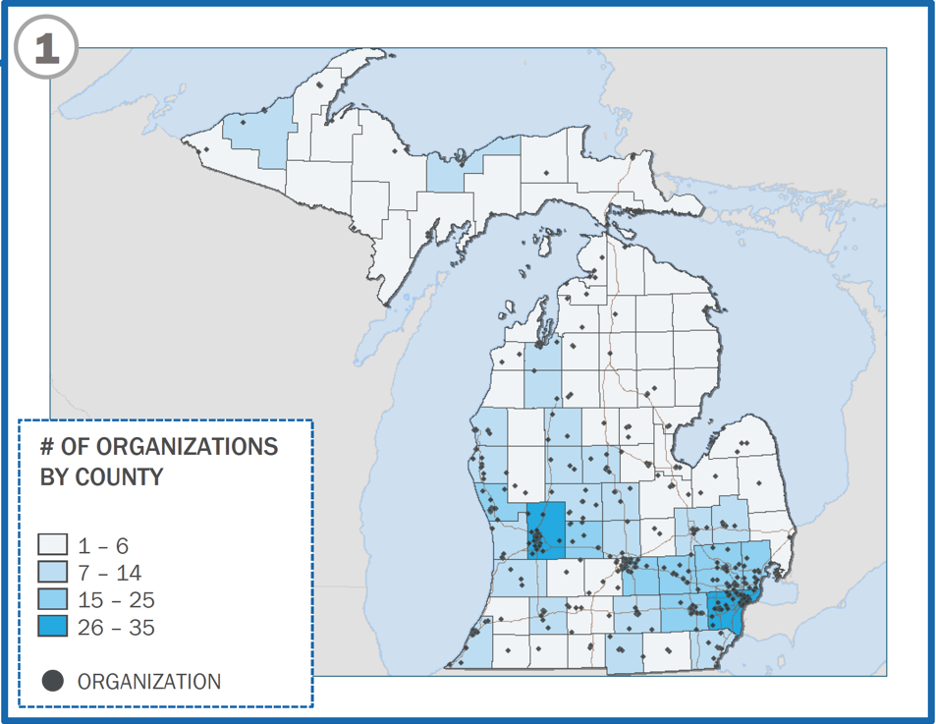

The report also mapped out where these interventions are taking place, finding that every county in Michigan is being served by at least one food program, with 64% of counties being served by six or fewer organizations. In general, counties with large cities have more interventions in place—26% of all identified interventions are taking place in Grand Rapids, Detroit, Lansing, Flint, or Traverse City.

Most interventions primarily focus on low-income, urban, or rural populations.

…BUT SOME POPULATIONS AREN’T GETTING ENOUGH SUPPORT

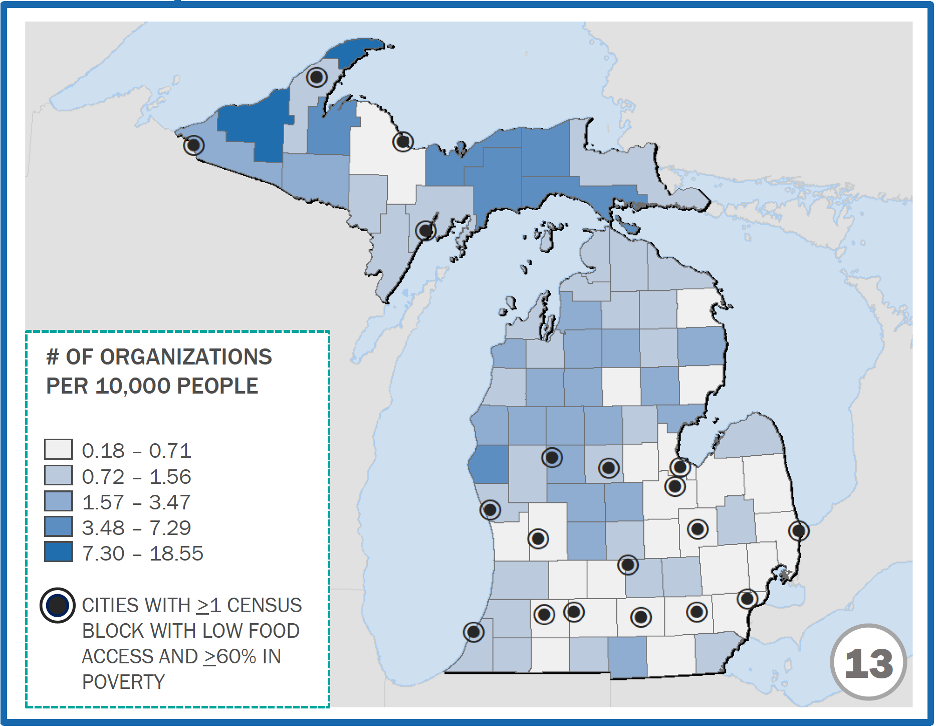

Bringing secondary data into the map—distance from grocery stores, socio-economic status (SES), population, and SNAP benefits usage—helped MPHI better interpret their data and identify geographic gaps. Their methodology was robust, and worth reading about in the full report. Step by step, they explain how layering this data revealed underserved areas.

The first phase of their process included identifying areas of the state with food deserts and with low SES. With those two factors together, seven areas with overall low SES, high SNAP benefits usage, and food deserts were revealed: Bay City, Benton Harbor, Flint, Jackson, Muskegon, Port Huron, and Saginaw.

Next, MPHI added the food intervention data into the equation and adjusted for population size. Layering that with the previous findings revealed 11 cities whose interventions don’t cover the need: Ann Arbor, Battle Creek, Bay City, Detroit, Grant Rapids, Flint, Jackson, Kalamazoo, Marquette, Port Huron, and Saginaw.

That’s not to say that no work is being done in those locations—there is. But the interventions there haven’t caught up with what’s needed. As one of MPHI’s informants said: “I don’t know if anyone is being left out. There is someone doing something in every community. I just don’t know if there is enough of it.”

IN THEIR OWN EYES

In addition to this empirical, data-driven approach, MPHI interviewed 16 individuals from 14 organizations involved in this work. They asked about successful and innovative projects in Michigan, what makes them successful and innovative, and where they see gaps in the food space.

Interviewees listed a variety of examples of effective interventions. Some—like the Food Policy Council and the Michigan Good Food Charter—represented broad, policy-focused efforts. Others—the Marquette Food Co-Op and Flint Fresh Food, for example—were centered around growing, sourcing, distributing, and retailing food.

Common themes for successful interventions included partnerships, scalability and replicability, economic benefit, and tailoring to local needs and culture.

In terms of gaps, interviewees noted some populations that, in their view, require increased attention: migrant workers and immigrants, language minorities, people above poverty level who don’t earn a living wage, older adults, small farmers, school-aged children, rural African-Americans, and tribal communities. Geography gaps they suggested included the Upper Peninsula, the northeast region of the Lower Peninsula, and counties south of I-94.

The interviewees also mentioned strategies that they would like to see more of, including policies and programs involved with school-aged children and school settings; large-scale, collaborative initiatives that strengthen food systems, local economies, and access to healthy food (like food hubs); and expanded investment in programs that match funds for food purchases in community settings (like 10 Cents a Meal).

Other key stakeholders, upon seeing the report, came up with three key takeaways for the future:

1. Focus on locally-driven, culturally-appropriate interventions.

These projects help communities reclaim and sustain power in food systems, and they recognize food’s deep cultural roots.

2. Define what “success” means to you.

Stakeholders noted how each organization’s definition of success was custom to their own community’s needs and priorities.

3. Consider this report’s findings.

Knowing where the needs are and being intentional about the impact of an intervention will help to maximize success.

In Conclusion

The Michigan Food Environment Scan brings a wide-angle view of food access needs during a pressing time for food systems across the state. Hundreds of organizations are already bringing effective, innovative work to the highest-need communities in Michigan, but there is still more to be done. Addressing these gaps will require local programming as well as large, statewide changes.

Moving forward, the Health Fund will use this information to identify programming and strategic partnerships in underserved areas of the state to help close these gaps. Through these targeted relationships—perhaps with unconventional partners—we hope to better position Michigan’s food system to strengthen food access in all communities.

The report answers our key question—who’s getting missed—and it goes a step further, suggesting what it will take to right the ship. As usual, the remedy is a complex mix of collaboration, community focus, and system-level change. Every new intervention in those categories gets us a little closer to the answer we want to say: no one.