The food-as-medicine approach to nutrition is gaining momentum throughout the country, with schools and health organizations developing programs that emphasize the preventative or even curative properties of healthy foods.

But for the Federally Recognized Tribes in Michigan and the Inter-Tribal Council of Michigan (ITCMI), the movement is less of a new development and more of an expression of a long-standing tradition—one in which diet and medicine have long been intertwined.

“The Anishinaabe elders teach us that eating the right foods at the right time can cure and prevent sickness,” ITCMI’s Michelle Schulte said. “Many of the cures our traditional healers give to people who are sick or struggling with disease are plants that have been hand-harvested from the wild. These plants are full of a number of vitamins and nutrients that work with our body to heal it.”

It’s in that spirit of healing that the Tribes and ITCMI have created their own nutritional initiative, Mishkikiiwan Miidjim, or “food as medicine” in the Anishinaabe language. The project—an extension of the Michigan Tribal Food Access Collaborative, which started in 2017—aims to curtail the childhood obesity crisis, an epidemic common throughout the country but one of particular concern to Native American communities, whose populations often have much higher obesity rates than average. According to ITCMI, over 50 percent of children in their seven Head Start programs are overweight or obese, and with the high risk of associated health conditions like diabetes and heart disease, a thorough and timely response is crucial.

With systems integration, nutrition education, and efforts to increase food access, Mishkikiiwan Miidjim has similarities to other food-as-medicine initiatives like that from Flint Fresh. What makes this program stand out, however, is its effort to weave the familiar food-as-medicine approach with the traditions and history of the tribes’ cultures, merging the wisdom of the past with the research of the present. Shulte, director of the Mishkikiiwan Miidjim project, says bringing this cultural framework to nutrition lessons is essential.

“Teaching nutrition in cultural context makes it more interesting because it connects you to the food you eat without complicated scientific terms,” she said. “It creates greater value because you understand how tied we are to our food sources.”

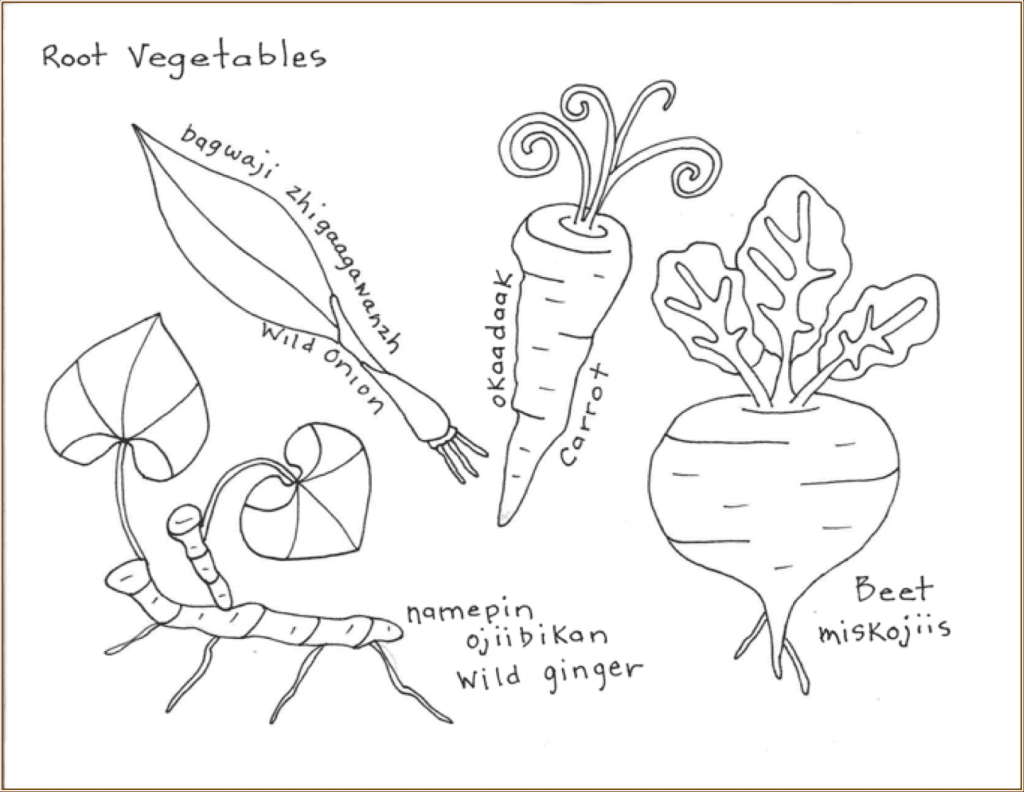

How are they teaching that connection? It’s called the 13 Moons curriculum, developed by the White Earth Nation, an Anishinaabe tribe in Minnesota, and adapted for use in Michigan. Once each month for 13 months, children in grades K–6 learn about a food important to the Anishinaabe people, with a curriculum-trained teacher introducing them not only to the featured topic’s nutritional benefits, but also to related Anishinaabe language and history.

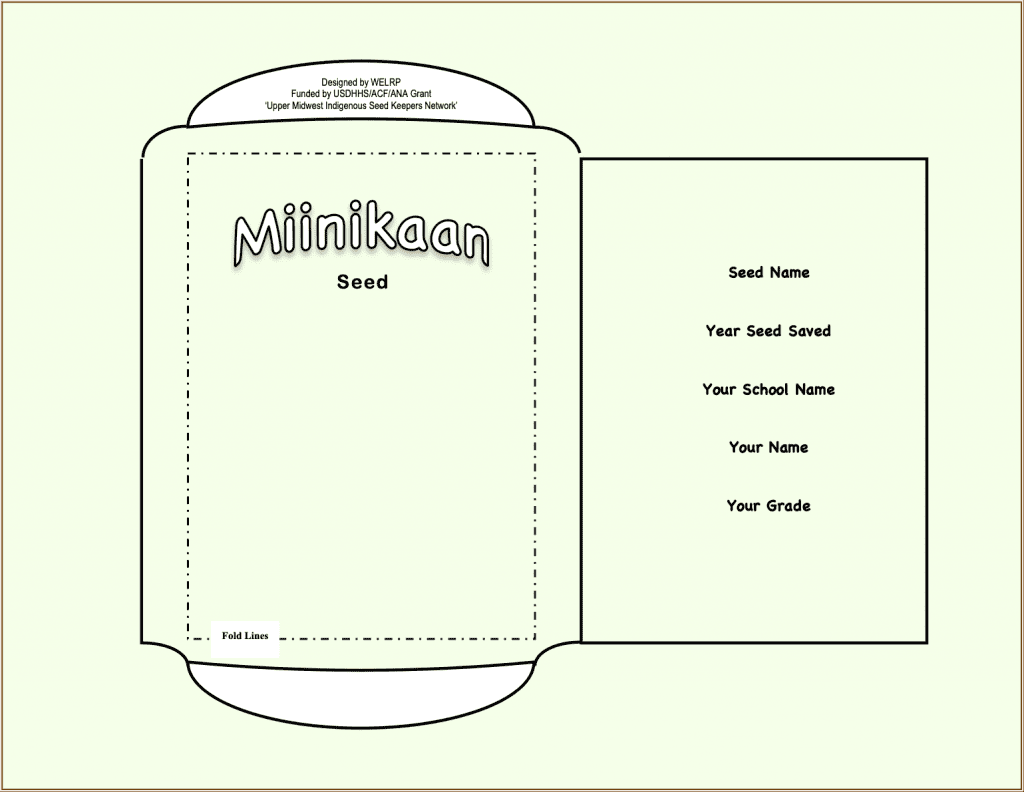

Topics included: the discovery of wild rice, the connection between corn and beans, the Anishinaabe relationship with the sunflower, and much more. On top of that, hands-on activities from coloring books to seed-saving and food-tasting promise to engage students and, with some luck, even convince them that healthy eating can be fun.

The 13 Moons curriculum is one of a handful of interventions ITCMI is putting into practice through Mishkikiiwan Miidjim. They are pairing the education with partnerships between tribes and local food resources, trainings for clinics to screen for BMI and food insecurity, and an expanded electronic health record. All of these efforts will build on the strides already made by the Michigan Tribal Food Access Collaborative.

The project’s underlying theme of cultural preservation is crucial, too. It joins various other statewide efforts to preserve Native American traditions while simultaneously promoting health. For example, another Inter-Tribal Council of Michigan initiative is combatting high infant mortality rates through traditional tribal practices. A different tribal collaborative has worked to promote food sovereignty and bring back wild rice in Detroit and elsewhere. And through another 2019 Health Fund grant, the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community is promoting intergenerational learning through the Debweyendan Indigenous Gardens.

Each of these projects has its own vision of what a healthier future will look like. For leaders of the Mishkikiiwan Miidjim project, that vision is a healthy food system, one in which nutritional concepts are familiar, nutritional food is accessible, and organizations like schools and clinics work together to monitor and improve the health of the community. To Schulte, that vision is also a call to connect with Michigan’s land, land that has been there for so much longer than any of us have.

“It is our hope that by sharing this wisdom and connecting it with others who also have similar wisdom, we can restore our own health, identity, and connection to our ancestral lands,” she said. “For those who may be descended from other cultures and immigrated to this continent, we invite you to also make a connection to the land in a greater way and allow your roots to go deeper than just what you see on the surface . . . The Anishinaabe people still have a lot to offer when it comes to living a healthy lifestyle.”

Photos from the Inter-Tribal Council of Michigan